“Why study cacao and chocolate?” read the slide. Dr. Carla Martin of the Fine Cacao and Chocolate Institute (FCCI), who is pioneering specialty guidelines for the chocolate industry, stood in front of the assembled crowd at InterAmerican’s Providence office one September evening. Looking resplendent in a hoop-bottomed cobalt blue dress from Kenya, Dr. Martin spoke about the incredible volumes of cacao and chocolate traded each year.

Coffee involves the lives of 25 million smallholders globally, while 5 million smallholder farmers grow cacao worldwide and 50 million people’s livelihoods depend on it. Further, Dr. Martin explained, the ways in which smallholder farmers receive compensation for their cacao is, as in coffee, often uneven and unsustainable.

Earlier, Dr. Martin and I had chatted about her career, which began with studying ethnomusicology and language acquisition. Soon, though, while conducting research in Western Africa, she began speaking with cacao producers about the knowledge and skills they wanted to access. Overwhelmingly, they reported wanting clearer information about cacao defects—how to detect and mitigate them—and on the determinants of quality.

As in coffee, quality and present defects in cacao are directly tied to the price producers receive. But unlike in coffee, there are no clear guidelines for determining quality, identifying and marking defects, or grading cacao. This absence leaves grading and pricing wholly up to individual purchasers. Farmers often reported sending their beans to 12 different buyers and receiving a dozen sets of feedback so different as to be unrecognizable as describing the same bean.

Dr. Martin concluded that something needed to be done about cacao grading and quality enforcement, and she founded the FCCI to begin addressing industry standards.

Chocolate, defined

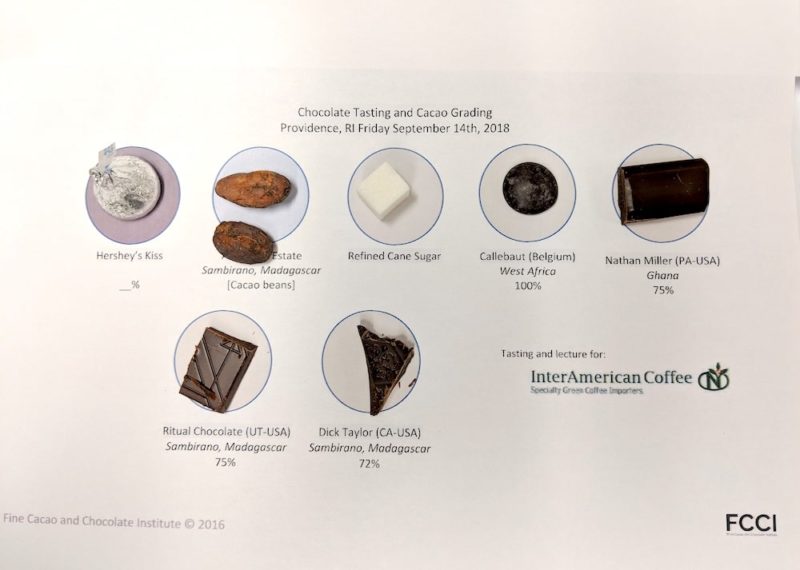

With the lights dimmed low, dozens of guests sat cradling chocolate sampler plates as Dr. Martin spoke. The willpower it took to abstain from eating the samples was enough to move a mountain, but we prevailed. The first sample we tasted came as a quirky surprise in a craft-chocolate tasting: the humble Hershey’s Chocolate Kiss. Composed mostly of sugar and milk with 11% cacao, the Kiss is, generously, considered chocolate and falls low on the quality scale of chocolate products.

It’s a prime example of the wide range of quality in the chocolate industry. The FDA specifies that chocolate products must contain at least 10% cacao to be considered chocolate, so at 11%, the Kiss scrapes a passing mark. “Imagine if your coffee were just 11% coffee,” Dr. Martin pointed out.

And what exactly does saying “11% cacao content” really tell us? A lot less that you’d think. “All it tells you is that the chocolate is 89% sugar [or milk products],” said Dr. Martin. As it turns out “cacao content” can also include cocoa butter. Eleven percent cacao could in fact be just 7% cacao and 4% (or more!) cocoa butter.

On the other end of the spectrum, we tasted chocolate liquor. Not to be confused with chocolate liqueur (chocolate-infused alcohol), chocolate liquor is about 50% cocoa butter and 50% chocolate solids (what remains when the cocoa butter is removed from the bean). This is considered modern chocolate in its purest form—100% dark chocolate. The chocolate was surprisingly smooth and melted quickly in my mouth and on my fingers. It was rich and bitter and had a lingering cocoa powder aftertaste. For many, it was the favorite chocolate of the evening.

After tasting two ends of the spectrum, we went back to the source. As we all wrestled with the thick, tenacious outer skins of the cacao pods on our sample trays, Dr. Martin spoke about the growing and harvesting processes of the cacao pod. For me, the most unexpected fact was that cacao pods sprout from the trunk and thickest branches of the trees, rather than the thinner branches most fruits grow from.

After grappling with the outer skins, we were rewarded with the dark sheen of the cacao nib. These beans were from Madagascar and were characterized by a high acidity and fruitiness that was quite pleasant. In an exciting comparison, we then tasted fully processed chocolate bars that were crafted from the exact same variety of Madagascar bean. I could recognize the same fruitiness and acidity in the bar as in the bean.

We tasted other chocolate bars as well, from cacao beans grown around the world. One bar tasted strongly of dried fruits, like raisins and dates, while another was like fresh stone fruit. Tasting bars from different places and experiencing the wide variety of flavors that can be found in cacao grown in different soil and climates demonstrated the effect of terroir, or place, on the taste of cacao. Just as in coffee, cacao grown in Kenya is very different from cacao grown in Brazil.

Coffee quality and terroir

During the second half of the evening, we tasted two flights of coffee, curated by our QC coordinator, Amanda Armbrust-Asselin. The first consisted of two coffees, a Mexico Robusta and a lower-scoring specialty coffee from Honduras. The goal was to get people chatting about different scales of quality and taste. Some people liked the Robusta, finding it closer to what they were accustomed to drinking, while others could barely palate it.

This variation in taste preferences highlighted the capricious nature of grading without calibration. When cacao farmers send their samples to chocolate makers, there is no metric for calibration, leading to a wide range of responses. Whereas the intense calibration in coffee found through the Q Grader test, cupping standards and the SCA and CQI scoring sheets ensure that coffee growers will receive more uniform feedback on quality of their coffees and purchasers can be clear about what they’re buying.

For the second flight, we tasted three high-quality coffees—from Papua New Guinea, Kenya and Guatemala—to highlight the power of terroir. These coffees included a wide variety of a flavors including fruit, nuts and even chocolate.

As we wrapped up the evening, people from coffee sought out people from chocolate, beginning a cross pollination of ideas and projects that will continue to blossom and mature over the coming months and years.

We thank Dr. Martin profusely for offering her time and expertise to our event, which concluded our 2018 Summer Sensory Series. As we enter the holiday season, we’ll take a break from events before resuming with a winter series in early 2019 that will focus on talks and presentations by specialists in coffee and related fields about sustainability, climate adaptation, the future of coffee and much more. We hope to see you there!

—

Victoria Brown is the QC Intern in IAC’s Providence office. While new to the world of coffee, she studied food history and food policy at Sarah Lawrence College. In her spare time she enjoys reading, knitting, drawing and cooking. Her full portfolio can be found here.